Emergency Preparedness: Do you have a plan in place?

While medical emergencies occur infrequently, they are 5.8 times more likely to happen in the dental office than in the medical office. Increasingly, more complicated patients are presenting to the dental office for procedures that are often deemed stressful. The dental interventions often take hours, increasing the risk of adverse events. It is therefore critical for dental offices to be adequately prepared for these infrequent occurrences.

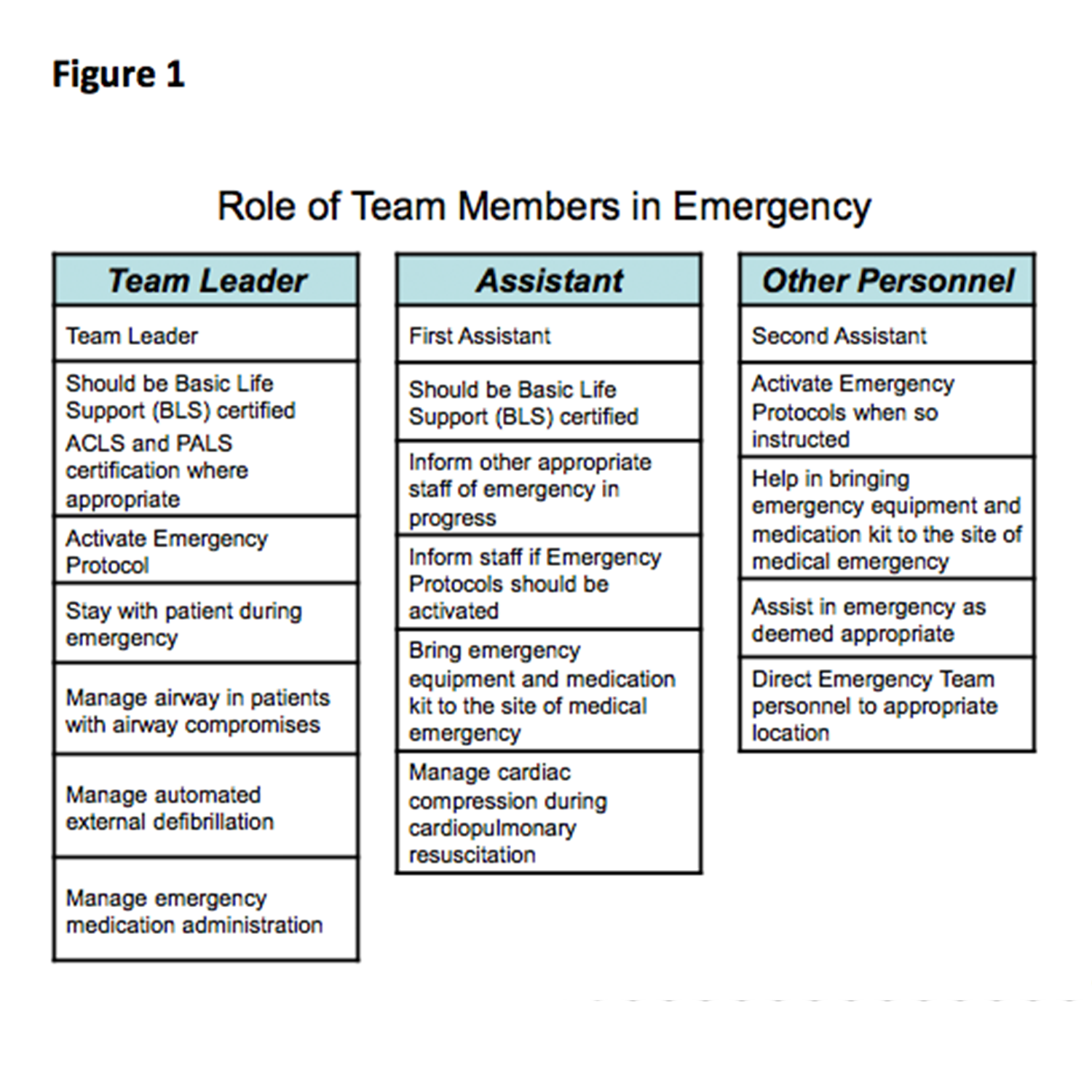

The role team members play during an emergency

Unlike in the hospital setting, where there’s a code team to attend to medical emergencies, you have a code team of ONE in the dental office. That’s why it’s so important to build an emergency team with your existing office staff. Thoughtful delegation of responsibilities will make medical emergency management that much more streamlined. A reasonable assignment of team member roles is presented in Figure 1.

I suggest you run mock emergencies to make sure every team member truly knows their role. This is often a morale booster for team members because they know they’re preparing for something critical in patient care.

Equipment and medication

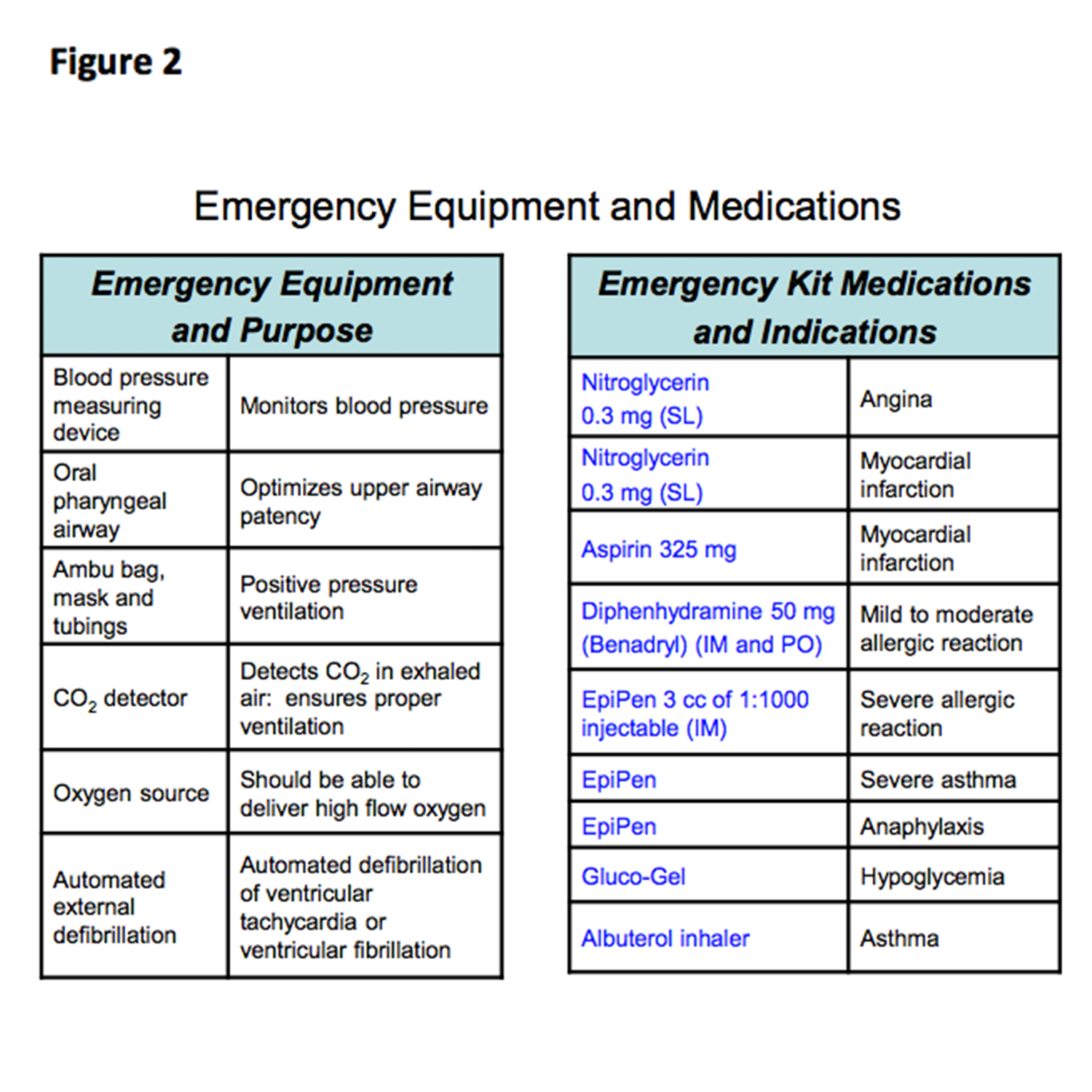

It is important to have certain equipment and medications for medical emergencies.

Equipment

By far, the most important piece of equipment you need is a reliable Automatic External Defibrillator (AED). Electrical shocks applied to dogs within 30 seconds of induced ventricular fibrillation (VF) produced a 98% rate of resuscitation. Electrical shocks applied to dogs after 2 minutes of FG) had only a 27% rate of success. Early defibrillation is now the cornerstone of resuscitation of acute cardiopulmonary arrest.

The latest renditions of AEDs are easy to use, have high sensitivity (>90%) and a very high degree of specificity (100%). It is important to purchase a machine that is capable of manual override. This modality permits you to manually shock a patient even though the rhythm interpretation indicates the patient is in asystole and is therefore not shockable. If a patient has an unwitnessed arrest and is in asystole for protracted periods of time, the override is obviously inappropriate. However, when cardiopulmonary arrest occurs in a patient who has had a witnessed arrest, the hope is the asystole actually represents fine ventricular fibrillation and can be successfully defibrillated by using the manual override option.

Although AED is very easy to use, dentists and their team members need to be trained to use the machine. The AED should be checked periodically to ensure proper maintenance.

Other equipment important for managing medical emergencies are listed in Figure 2.

Medication

While there are fancy drug kits you can purchase, it is important to understand that six drugs alone can bail you out of 95% of all medical emergencies. Having drugs in your kit you cannot use (for instance, IV administration for most offices) or that you do not know how to use increases your liability without benefitting your patients.

The only six drugs you need to know about and learn to use are listed in Figure 2. Familiarity with the use of these drugs and an understanding of their side effects allows dentists to handle many of the emergencies encountered.

Cardiac Arrest

The most dreaded of all medical emergencies is the occurrence of cardiac arrest in the dental office.

The 2015 guidelines can be implemented with the team and equipment I have delineated.

If a patient becomes unresponsive or has abnormal breathing, you should assume the patient may be having a cardiac arrest and activate the emergency team. The second assistant should activate the EMS.

The patient should be moved to the floor, where a firm surface allows for effective cardiac compression.

The dental professional should initiate compression immediately while awaiting the emergency equipment to arrive on the scene. Compression, Airway and Breathing (CAB) supplanted the previous Airway, Breathing and Compression (ABC) algorithm in 2015 because there is data that shows delaying first compression is associated with a worse outcome. As soon as additional members of the team arrive, the dental professional should be at the head of the patient and responsible for managing the airway and for providing oversight of the proceedings. The first assistant will assume the responsibility of chest compression.

Compressions should be at a rate of 100 to 120 compressions per minute and should be 2 inches (5 cm) deep to be effective, but not greater than 2.4 inches (6 cm) to avoid complications.

The team should progress to AED deployment as soon as the emergency equipment is brought in by the second assistant. Early defibrillation has been shown to be critical in successful and meaningful resuscitation.

With the emergency equipment recommended in Figure 2, the dental professional should place an oral pharyngeal airway (OPA). Proper airway can be completed by picking the airway length that spans from the bottom of the patient’s pinna to the corner of the mouth. The OPA should be inserted upside down and flipped over when it is fully inserted. This minimizes the likelihood of the back of the tongue obstructing the upper airway.

Once the OPA is in place, the first assistant should hand the mask to the dental professional, who then ensures the patient’s chin is gingerly moved up and forward and that the mask fits snugly around the nose and mouth. Positive pressure ventilation using an ambu bag with high flow oxygen should be started. In this situation, there should be 30 compressions and two breaths.

At all times, interruptions to chest compression should be limited to less than 10 seconds.

In a patient with a witnessed arrest, the ability to override the AED is important when the AED reports the patient is in asystole and does not have a shockable rhythm. The hope is the asystole actually represents fine ventricular fibrillation and can be successfully defibrillated by using the manual override option.

The second assistant should assist with equipment retrieval, drug administration and relieving the first assistant in chest compression.

This team approach, combined with using the recommended equipment, should ensure optimal cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the dental office.

Managing medical emergencies in your office

Using these guiding principles, you should be comfortable managing the infrequent medical emergencies in the dental office. Emergency preparedness will save lives.

Managing Tooth Wear

Tooth wear is a common yet challenging condition in dental practice. This guide offers detailed insights into diagnosis and treatment, addressing overlaps with medical conditions and providing practical, actionable advice. Discover why Dr. Shepperson is known as the "tooth wear dentist."

You May Also Like

Root Canal Treatment: Radix Entomolaris

Measuring Tooth Wear: How To Use a Simple Index

By: Dr. Leslie S.T. Fang, MD PhD

By: Dr. Leslie S.T. Fang, MD PhD