In the first installment of this two-part series, I discussed the value of estimating root length and offered insight into some unrecognized challenges that may affect case selection. But once cases are selected, the skill of establishing radiographic estimates continues to carry forward to clinical treatment.

The Value of a Depth Estimate

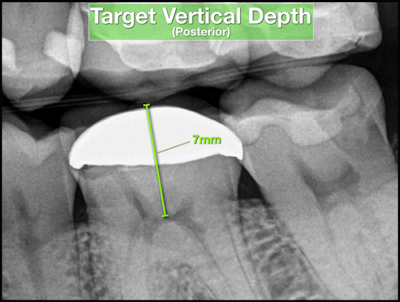

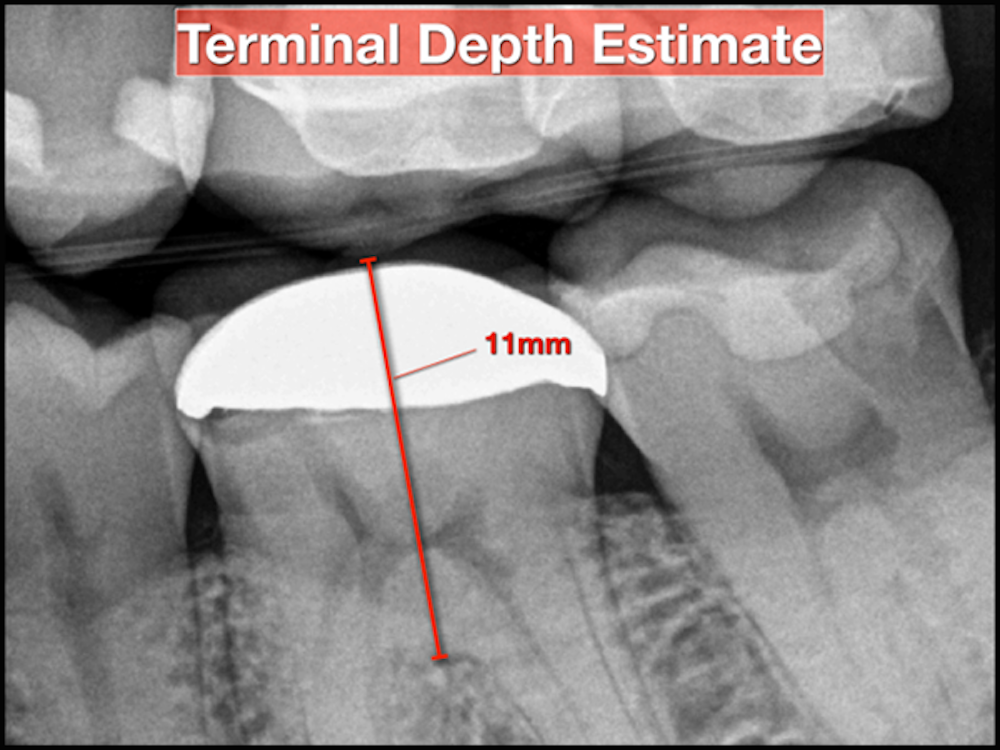

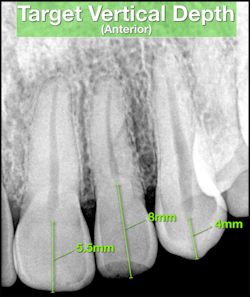

Before initiating treatment, an estimate can be made from the tooth’s occlusal surface (or incisal edge) to various levels within the tooth. This estimate represents a “target vertical depth” and can assist with endodontic access when measured to the roof of the pulp chamber (Fig. 1). In multi-rooted teeth, an additional “terminal depth estimate,” measured to the furcation, could help avoid iatrogenic perforation (Fig 2).

A bitewing radiograph is considered to be the most spatially accurate and dimensionally stable image with respect to 2-dimensional radiography, making it ideal to estimate the depth when treating posterior teeth. Estimates for anterior teeth must be determined from the slightly more distorted periapical radiograph (Fig 3). This visual exercise can also influence case selection.

Pulp chambers appearing small, constricted and/or non-visible are typically more challenging to treat and must be recognized.

Gauging Depth

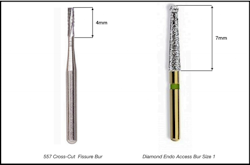

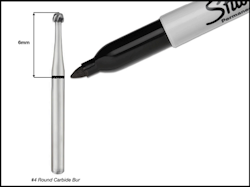

Target vertical depths and terminal depth estimates only have value when used in conjunction with a method to gauge depth. Two methods are available. One method involves the use of a bur with known length dimensions. Many different types of burs can be used to create an initial endodontic access. The active cutting surfaces of straight carbide-fissure burs and/or straight diamond coated burs have consistent measurable lengths that can be used as reference (Fig. 4).

Round-type burs and/or straight burs with shorter working flute distances can be premeasured and marked with an indelible marker at the target vertical depth (Fig. 5). The other method involves the use of a periodontal probe and the periodic verification of depth as the bur is advanced toward the pulp chamber. In some scenarios, both methods may be indicated.

The access bur should not be advanced beyond the estimated target vertical depth. Once the estimated depth has been achieved, the clinician should visually inspect the access for signs of the pulp chamber with a DG 16/17 endodontic explorer (Fig 6).

If the pulp chamber is successfully identified, an endodontic specific, safe-ended access bur (Fig. 7) should be used for access refinement. If the pulp chamber has not been identified, a radiograph should be captured to verify current depth and proper orientation.

Appropriate angulation adjustments and/or updated depth estimates should be considered based on the current radiographic information. In multi-rooted teeth, caution must be exercised when nearing the terminal depth estimate to avoid perforation. It is considered clinically acceptable to initiate an endodontic access without rubber dam isolation. Once the pulp chamber is identified, appropriate aseptic protocols should be followed.

Enhanced Predictability

Our training has taught us to evaluate periapical radiographs for radiolucency, widened PDL spaces, number of roots and root curvature. We us bitewing radiographs to identify carious lesions, broken down and/or ill-fitting restorations and occlusal relationships. The value of these images extends far beyond these institutionalized givens with respect to case assessment, case selection and the application of endodontic technique. The ability to leverage these images for the purposes of length and depth estimates can significantly improve predictability in the early phases of endodontic treatment.

By: Dr. William J. Nudera DDS, MS

By: Dr. William J. Nudera DDS, MS